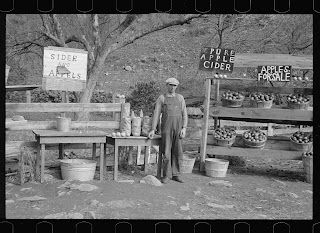

The Sweet Briar screening on Wednesday evening was important for two reasons. First, Sweet Briar played its own role in eugenics. One of the authors of the famous eugenic book, Mongrel Virginians: The Win Tribe (1926), had been a Sweet Briar Professor just before its publication. The Win Tribe focused on a poor interracial community in Amherst County so called 'WIN' due its 'White, Indian and Negro' heritage. Its authors falsely connected the community's poverty to this interracial makeup. Funded by the Carnegie Institution in Washington, DC, The WIN Tribe's lead author was Arthur Estabrook. Below is a link to an image from Estabrook's photograph's of The 'WIN Tribe. ' Estabrook kept a scrapbook of photographs as part of his 'documentation.' His photographs reflect the role of photography in eugenic studies.

|

| "Callie Black" from Estabrook's Scrapbook |

http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/1255.html

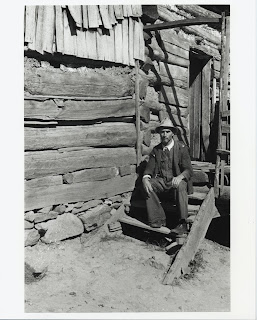

The second reason the screening was important was that it was attended by Mary Francis. To a large degree Mary Francis is Rothstein's First Assignment's central character. Though her appearance comes at the end of the film, it is her family that was a the center of Rothstein's First Assignment. Virtually all of her aunts and uncles had children that were sent to the Colony. For reasons that are still not clear, Rothstein gave more attention to her family than any other.

At the age of 7 she was sent to the Colony in Amherst County where she was forcibly sterilized. As Mary Bishop reported, the operation almost killed her. Mary wasn't released from the Colony until the late fifties. She believes her marriage dissolved because she couldn't bear children.

Having Mary Francis at the Sweet Briar screening of Rothstein's First Assignment was also important for Mary Francis. Mary Bishop, who has reported extensively on eugenics in Virginia and first reported Mary Francis's story, explained to me that most former residents of the Colony slip into obscurity. The shame that comes with being labeled "feebleminded" creates its own exile. Few are willing to talk about their experiences. Of the thousands of individuals who were sterilized in Virginia, only a handful have been willing to go on the record.

When Mary Bishop heard that Mary Francis was going to come, she decided to also attend. She wanted to witness the event. It was an emotional experience for everyone. Mary Francis's caretaker was so moved that she cried.

|

| Mary Bishop with Mary Francis (seated) at Sweet Briar |

The second historic screening occurred as part of the Virginia Film Festival in Charlottesville. On Nov 5 at Vinegar Hill Theater in Charlottesville, Rothstein's First Assignment opened to a packed house. The screening had sold out the day before and by some counts there were over 60 people without tickets who wanted to get in. Even those of us on the panel had difficulty getting tickets for our spouses.

Part of the reason it was so popular was that RFA had received a large amount of press leading up to the event. The local paper, The Daily Progress led with RFA in its coverage of The Virginia Film Festival ('Rothstein's First Assignment' examines documentary truth). Sandy Hausman of NPR covered it (A Dark Part of Virginia's Past Comes to the Big Screen) while even the local TV station, Channel 29 picked it up (Experimental Documentary Tells a Different Story).

The other part of its popularity likely had much to do with the fact that Rothstein's First Assignment is largely a local story. Many elements of the story connect with Charlottesville and the University of Virginia. The social worker, Miriam Sizer who apparently worked with Rothstein (she was photographed by him) received her Masters from UVA. While Shenandoah National Park is popular with Charlottesville residents.

There was also the local support of Madison and Orange Counties. In what has been a bit of a surprise, there has been more support than I anticipated from descendants of mountain residents who were displaced when they created the Park. I had feared that with the unorthodox approach I took in making the film (it was originally intended to be an experimental film), I would lose this local audience. In my efforts to have RFA structurally explore the idea of documentary truth while it conventionally questions the 'truth' of Rothstein's assignment, I feared I might alienate local residents.

To my surprise it turns out that they have given Rothstein's First Assignment a large amount of its support. Indeed at a screening in Madison one descendant came to my defense during a Q and A asserting the truth of the sterilizations, while a viewer at a screening in Orange asked how she could have her daughter see it. Local screenings have often brought to light stories unknown to me.

As case in point, though Rothstein's First Assignment has been screened locally three times, there were still surprises at the Virginia Film Festival. For one I was able to fill in a missing link in one of Rothstein's photographs. A woman came up to me after the screening and identified her mother in one of Rothsteins's images. Most of the children are not identified in Rothstein's captions making it difficult to track them down. While during the Q and A after the screening, a man made a claim that individuals from UVA were not only connected to eugenics, but also to the famous Tuskegee experiment. A claim I had not heard before.*

_________

* It has been brought to my attention that Paul Lombardo explains the link to Tuskegee in an article with Gregory Dorr titled, Eugenics, Medical Education, and the Public Health Service: Another Perspective on the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.